I

My move to central Harlem has produced explanatory inadequacy: I’m groping for words. It’s also produced the experience of revelation and amazement—every block has some architectural marvel, if you’re not stopping to gape at these buildings, you’re not looking, you’re just walking, trying to get from one place to another. If you’re not acting like a tourist or an archaeologist, in other words, you’re missing something. But what kind of lede is that? What am I, some romantic poet in the Lake District, dilating on a warm afternoon, looking out over a babbling brook?

No, I’m sitting here on 123rd Street, looking south over a wide counter into a well-equipped kitchen, listening to Amy Winehouse sing “Love is a Losing Game,” and yes, I play it over and over, just like I played the Jackson 5 over and over back in 1970, because as always my question is, How do they do that? How did they cross over?

There’s a moment in “Losing Game” that’s heartbreaking, and it’s not the moment when the singer self-consciously stutters in the third verse, no, it’s in the second verse, it’s when the strings enter and swell, she describes love as “self-professed, profound,” and then she says “’Til the chips were down,” waits for you to catch up, and finally she sings “Though you’re a gamblin’ man . . . love is a losin’ hand.” How does she do that, how does she convince you that someone—not just anyone—bet on you and you betrayed her? How does she sing the blues?

Is it the timbre of her voice, which is determined by the narrative structure of the song? There’s an anonymity, almost an anthropological quality, to the sound of “self-professed, profound”—it’s an observation any intelligent person might make if rhyme and meter were important dimensions of her utterance. The voice ascends the scale in the second syllable of “profound,” and then starts a slow descent: the rhymed words (“profound/down”) hit the same note, but their meaning has changed because the temporal position of the singer and the address of the listener have, and these new locations register in a barely perceptible vocal emphasis on where those poker chips are in time.

The fourth word of the transition is the giveaway: if you’re still singing in the abstract about the profession and the profundity of love, if this is a pop song, you say, “Til the chips are down.” Instead she says, “Til the chips were down,” and she draws out the word so now you know she’s singing about a real event—one that has taken up residence in a narrative that gives it meaning—and this formal occasion is marked, fleetingly but unmistakably, by the descent into a deeper, more quavering vocal timbre. When she turns to address her lover as a gambler, that descent into time is recapitulated vocally and again fleetingly by the first word: “Though.”

See what I mean about groping for words? If you’re not reading between the lines, you’re not understanding anything, because how you say something determines the way it will be received: the form of your utterance doesn’t merely reveal the content of your thinking, it determines that content, it dictates what your listener can hear, or what your audience can listen for. It’s not an either/or, of course. But still. A picture is worth a thousand words, right? How’s that? Same principle.

II

The ambiguities that attend my new residence—talk about reinstating the vague, as William James wanted us to—derive from a realization, in both senses, of privilege. I can afford to live here, or rather buy a place in this neighborhood, whereas most of the people on my block can’t, and I understand my “distinction,” as Pierre Bourdieu might say, following Thorstein Veblen, the delinquent step-child of American higher education. I think about it, anyway, this privilege. There’s a word for what it means as a demographic shift, but it doesn’t capture the phenomenon as I’ve been experiencing it: gentrification, there’s that word, ugh.

Yesterday I went to two grocery stores, count ‘em, one on 125th just east of 5th Ave, the other on 8th Ave just south of 119th. Notice how I’m still orienting myself in Midwestern fashion, north and south as against uptown and down. Both of these stores cater to thoroughly bourgeois people like me—there you’ll find fresh bread and bagels, home-made lox spread, craft beers, strange produce, wild fish from Alaska, but the difference is palpable, measurable, can I say physical?

On 8th Ave, where security guards stand watch at the entrance and the exit of Best Market, new business is everywhere, and unexpected offerings sprout daily—bakeries, bars, wineries. Monday night I was with my neighbor Cassandra at a place opened just three months ago, Ugly Dog Pizza—I’m not making this up—and the proprietor predicted great things for the block even though the traffic was slow in his place. Skinny bald white guy, I don’t know, can we trust his judgment? Him, not me. Maybe.

Cassandra and I sat at the molded metal bar, making fun of the people, mostly families, at the tables. Her friend Farleigh, as in Dickinson the university, joined in, meanwhile remarking that being in love is better than the alternatives and that having more kids is something she really wants to do. I questioned her sanity, of course, but her answers seemed cogent if not convincing. I referred her to a book called Against Love, and in Googling the title, she decided, as later told to Cassandra, that the author was “very attractive.”

A month ago, Cassandra took me to a beer garden (run by a real European) on 114th, and 8th Ave, where we met up with her entrepreneurial friends from the neighborhood—the husband organizes basketball tournaments around the world where sports clothing sponsors assist the scouts in identifying talent (he used to play in a South American professional league), the wife supplies the accounting chops and the chutzpah—and sure enough, two weeks later we ran into them, their three kids, and their equally entrepreneurial friends over Sunday brunch at Sylvia’s on Lenox/MX north of 125th, where European tourists keep lining up to partake of the “soul food” once consumed by a black peasantry, and middle-class black families keep coming to perform a ritual of continuity with a diasporic heritage, which is the time etched into these old facades.

In short, the little Harlem renaissance now sponsored by gentrification is far from monochromatic: it happens in black and white, like the big one did. And to repeat myself: race is complicated by class in this part of the world, and vice versa. What is more interesting, for now, is that on both sides of the color line, the renovation—sometimes the mere visitation, don’t just laugh at those tourists—of the neighborhood or the block or the building is undertaken in the name of reclamation, and this even when the vision of an inviolate black Mecca in Harlem is offered by a toothless, homeless old man who sought shelter from these same mean streets on January 27th, 2009, at a sorry rehab joint on West 57th and 10th Avenue (as I recall, he was still on that fourth step, so his moral inventory is still changing unless he’s dead).

We’re all retrieving, reviving, reinstating, and rehabilitating, in a word, remembering, but this act changes everything about the past, in the present, and for the future. How do we cross over?

III

On 125th, where there’s no security, the Wild Olive Market just grooves. I can’t discern a pattern to the aisles, it’s as if you rolled the dice, summoned the genie, or conjured the wizard and found yourself in the midst of substances you’ll never understand—go ask Alice. You’re not quite on drugs but you could be, and you want to be. It’s like a jungle, but slightly less profuse (once upon a time I lived right next to a jungle in Panama, so don’t get all correct on me). Or a maze: there’s no discernible order here, but it was man-made, it’s as unnatural a habitat as you’ll find anywhere in the city. Do I contradict myself? Very well, then.

I prefer the Wild Olive, but that’s probably because it’s closer, and because walking down 125th is a trip unto itself. To call it time travel is not to indulge some science fiction metaphor, it’s to get realistic about where you’re headed—into the past. But then the question is, which one?

There’s no new business on 125th as you walk east from Lenox/MX. Except for the Applebee’s at 5th Ave—how did this get here, you ask, it looks like an alien craft on idle, just waiting to lift off again—you’ll see the same old same old: hats, shoes, T-shirts, African braids, rehab centers, got you covered. West of Lenox/MX, there are familiar stores and franchises galore (Staples, CVS, H & M, Lane Bryant, M.A.C.) but here, on your opposite way to the Wild Olive, it’s old guys selling CDs, DVDs, belts, and fragrances from folding tables, or it’s a narrow storefront selling exotic linen dresses that touch the ground. Also political persuasions, as in Lost Tribe of Israel or pan-African affiliations, and sometimes shrimp or mussels out of a cooler. The colors of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, the vibrant green, yellow, and dark brown that Marcus Garvey sponsored, are everywhere. These fade—they never quite disappear—when you walk west on 125th, toward Amsterdam.

I think it’s the working-class difference made by those public-housing projects I mentioned: east of Lenox/MX, you approach the towers that line Harlem River Drive (which becomes the FDR). When you get closer to Amsterdam, west of 8th Ave, the projects rise again. In the middle ground where I’ve settled, say between 5th and 8th Avenues east to west and 116th and 135th south to north, there’s a new mix of classes, and that changes the relation between races, and vice versa. These coordinates can’t describe the culture shock I feel when I have to dodge profuse white families in khaki shorts on 123rd just east of Lenox/MX and right off Marcus Garvey Park (it interrupts 5th Ave between 124th and 120th). The bourgeoisie, white and black, changes everything—and not necessarily for the worse, regardless of what Robin D. G. Kelley claims about Harlem under the hammers of globalization, in the smart foreword to a lovely, elegiac coffee-table photo book by Alice Attie called Harlem on the Verge (2003), which of course makes the visual case against the multinational interlopers who are driving the small, locally-owned shops out of business.

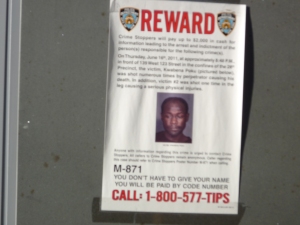

Or not. There’s a Police Department poster attached to my brand new building announcing a reward for information about the murder of a young man named Kwabena Poku on June 16th, at 139 West 123rd, that’s my side of the block four doors down, and just back of Cassandra’s apartment on 124th. He was shot “several times,” the poster states. His picture is the center of the poster. He doesn’t look innocent, he looks confidently into some official camera knowing his life will last beyond this booking, this photograph. His pose reminds me of the iconic images that made Robert Johnson famous, shoulders hunched, body gathered, but head up and eyes still shining, as if he’d just taken a deep breath and was going to test his voice and his ideas on you. Too late, you say, this life can’t be changed by its retrieval or remembrance. Or not.

IV

I invoke a “working-class difference” because I’ve been taught to by Harold Cruse, one of the most cranky and insightful writers of the 20th century. Back in 1960, he wrote a 100-page manifesto denouncing the baleful influence of the Communist Party on the black liberation struggle—it’s not his language, he was also dubious of “civil rights”—and detailing the centrality of nationalism among the “black masses,” as he called them. He sent it to a little magazine, Studies on the Left, published in Madison Wisconsin, where one of the founding editors cut it down to size and published it in 1962 as “Revolutionary Nationalism and the Afro-American.” Malcolm X read and admired it in that format, he later told this editor when on a visit to Madison. The article led quickly to a contract with Morrow, the result being The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967), Cruse’s huge, sprawling, strange, and brilliant book on—what?—everything that matters about Harlem and American history.

Here Cruse argued that the mainstream of black liberation was not the civil rights agenda of integration and assimilation, but rather nationalism—self-conscious cultural segregation, as W.E.B. Du Bois had urged in The Crisis (1934), then more passionately and effectively in Dusk of Dawn (1940). Cruse claimed that the “black masses,” the working class majority of African America, was always more attached to the sensibility—not necessarily the programs—of the UNIA than to the postwar civil rights agenda, even as late as the mid-1960s, and this claim is validated, I believe, by anti-colonial events (“riots”) in major cities before 1968 and by the appendixes to Gunnar Myrdal’s American Dilemma (1944), where, in wonder, everyone admits that Garvey built a mass movement that outstripped all others.

Cruse also argued that Marxism as understood by academics and CP hacks alike was useless in understanding the American experience, particularly but not only the African-American experience, because it insisted on the priority of class struggle no matter what the evidence allowed. He followed the example of C. Wright Mills and Daniel Bell, emphasizing what Mills called the “cultural apparatus,” and trying, always, to preserve the methods and insights of Marx without becoming a Marxist. So he’s still a pretty good example of intellectual anger and adventure.

V

Equipped, then, with the sociological lever Cruse provided, I have been prying at the class compartments of my new neighborhood, assuming it would reveal new dimensions of a racial situation. It hasn’t quite worked out as planned, and that is a very good thing.

For example, my Jamaican neighbors refer to the park over there as “Mount Morris Park,” its designation from 1840 to 1973, but so do the African-American owners of the beautiful brownstones who advertise and galvanize the neighborhood association under that very heading. It’s not Marcus Garvey Park as far they’re concerned, just like Lenox isn’t Malcolm X Boulevard, or 6th Avenue isn’t Avenue of the Americas, for anyone who actually lives in this place. But still, when I gestured interrogatively toward the park one day, having lost a bet to my neighbor on Traffic Code 40, the fire hydrant ordinance, everybody on the stoop drinking beer at my expense—there were seven of them—said “Mount Morris Park,” and when I said you mean, not Marcus Garvey, they all shrugged and said, “Yeah, Marcus Garvey,” as if the designation wasn’t that important.

My friend Bruce Williams the photographer from 596 Edgecombe, uptown on Sugar Hill, well, he says “Marcus Garvey Park,” he’s about my age and he’s been there a dozen times to take pictures of dancing crowds in the Richard Rodgers Pavilion—yeah, the Broadway composer paid for it, he grew up nearby—and so does my neighbor Cassandra, who is younger than Bruce.

Is it generational? Will the kids get used to the official labels that denominate this space, or will they be confused by the street signs that surround the park (Mount Morris Park West, etc.)? Is it political? I asked a guy selling the most extreme books and CDs on 125th—conspiracies abounding, meaning Jewish bankers are accountable for everything bad and Africans are attributable for everything good—what he called the park over there, and he said “What park?” He had three different and astonishingly bad books on Garvey for sale.

Or is it the American tradition of rehabilitating the dead radical? You know, Debs becomes the avuncular folk hero from the Midwest, Doctor King becomes the Messiah from the deep South, and Malcolm becomes the sober, imperturbable, almost professorial critic of racism from River City. Garvey was hounded, arrested, and deported by the US government for trying to get Negroes to invest in a pan-African shipping enterprise, the Black Star Line, which, as Du Bois grudgingly acknowledged, could have sutured the Atlantic to the economic advantage of black folk everywhere. He led the second, maybe the third, mass movement of African-Americans in modern times, after the General Strike of the 1860s that broke the Confederacy and (perhaps) the Populist revolt of the 1890s. In Harlem, he was a celebrity. The UNIA had close to 20,000 New York members in 1920, before that final wave of immigration from the deep South turned Harlem into the capital of black America.

But the neighbors, even the most civic-minded of them, say “Mount Morris Park” when prompted. A palimpsest, to be sure, as my girlfriend suggests. I want to say that the words themselves are layered, freighted with political significance—you’re making a statement when you choose one designation over another. But it’s not a choice if you’re unaware of the relevant history.

So I’m forced back to my original position: explanatory inadequacy. That’s OK. The only reason to write is to realize something just beyond your grasp, to put something into words that doesn’t belong there until you do. This dream of life is all edges, where everything that matters is evident yet unknown. If you’re lucky, you never wake up, you keep moving, pressing on those dangerous perimeters, and what you know in the end is all you can.

VI

I played dominoes with the old guys across the street last week. They put a piece of laminate on a garbage can and slap the pieces around, exclaiming and explaining as they go, when I wasn’t involved they innocently showed me their pieces like a hand of cards, always brandishing dollar bills because this is for real. It’s not like Havana or Washington Heights, though, where speed is the sign of expertise, here everybody takes their time and when the majority of pieces have gathered at right angles the players actually slow down to produce commentary, as if they’re auditioning to do color at ESPN. I lost money. I don’t even understand this game.

As I stood around and played dominoes with these old guys, I was thinking about the future of the neighborhood. Am I the harbinger, the physical measure of gentrification? Am I a historical marker (recall that my building was the site of the southernmost black occupancy as late as 1925)? Will this reclamation, this remembrance, change Harlem? Or is this place always on the verge?

To all of which I say, yes, of course, calm down. The crossing over is never done because the color line is never fixed.

Brilliant.

It could be the people of your neighborhood refuse to call the park by it’s given name because they demand recognition for their residency and ownership of that place, not just their presence there.

To say “we reside in and own this place” is to say “we belong here — it’s ours”. It means something more, I suspect, to be able to say “we own this place as it is and was, not just as the city council named it to mark our presence here”. It’s a way of asserting the plain fact of belonging to, as against occupying your own space historically – not just temporally.

At some level I suspect your neighbors think of Marcus Garvey Park or Malcolm X Boulevard a little bit like the rest of us think of all the thousands of public places that were suddenly renamed “Reagan” in the 90’s, or of the one street in damn near every southern town that was renamed “MLK Boulevard” in the last 30 years.

I know that in this town that street is called 1st Street by natives and others of a certain age, black and white alike. Whether “1st Street” survives depends on whether we continue to “own” this place, as your neighbors clearly own theirs.

Agreed, particularly about the emphasis on ownership. Still, I was struck by the unanimity of the natives, as it were, as against the settlers (Bruce, Cassandra, me, like most New Yorkers we came from elsewhere). And hey, how about them pictures?

This sort of thing is very complicated for me. I can see how a newcomer would defer to the sign on the fence or the street post in every case — and how they would continue to do so even after realizing that the “natives” don’t. For my part, I think I would do so as a way of marking myself as new — a guest so to speak. It’s pretentious to adopt a “learned” persons language, I guess. But that’s just common courtesy isn’t it? It serves us well to be a little self-conscious around new people.

On the other hand, where does the renaming come from? Is it safe to assume that leaders from Harlem lobbied for the changes to Lennox Av. and the park? Of course they did. Just as so many lobbied for so long for a national holiday for MLK. (And, call me paranoid but I have always thought that the hysterical drive to rename every other public space in the country for St. Reagan was, as much as anything, a reaction to the MLK Holiday)

But that’s the problem for me: I was guessing that your neighbors are saying “I just as much belong on “Lennox Avenue” as anyone who came before me! (and, I wonder, after me too?)” And that brings up the problem of patronization by local leaders as well as by the city council downtown. Uptown or Downtown, those leaders have something in common, and it ain’t their color.

Of course I could be all wet about this, but if what I’m saying is accurate then the simple answer might be that Harold Cruse was wrong: It is all about class after all.

Another way of testing that would be to ask whether a new resident to your neighborhood in particular is, by definition, middle class, and what that means to the people who already live there. After all, who buys property in Manhattan?

So the self-consciousness I mentioned is just acute class consciousness: felt by you and (or because it’s?) expected by them.

I should have made it more clear that I realize you got the same reaction from all the neighbors — Brownstone and project residents alike . But I’m not sure that newness to an expensive address doesn’t convey class superiority in and of itself. That’s also where the question of belonging being extended to those who come later seems like an open one.